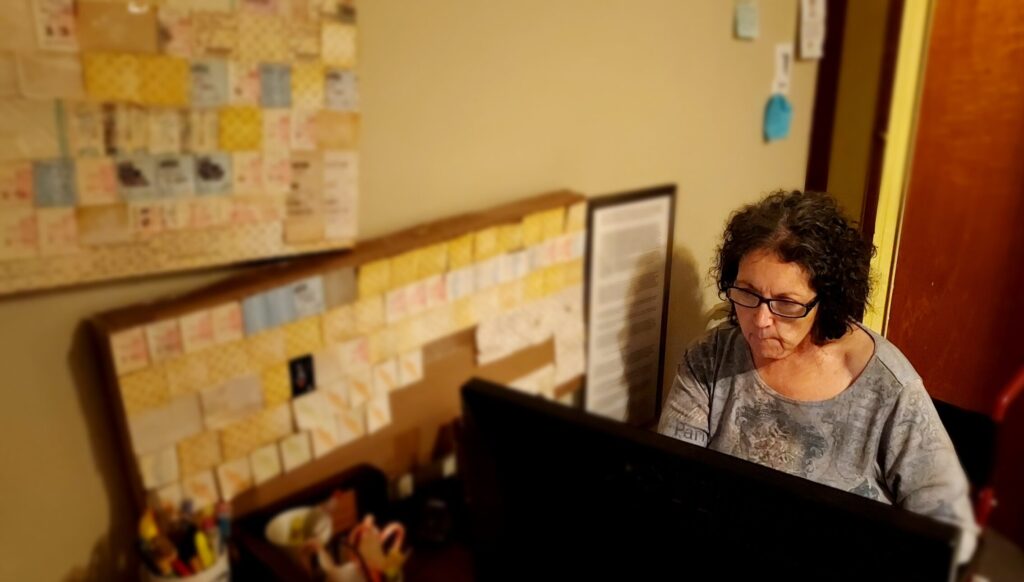

Janice Reads Her Work to an Audience for the First Time

I was really doing this. Sixty-three, and for the first time in my life stepping forward to read my poems to friends and neighbors gathered in this library eagerly looking to me. The accompanying three piece band began. I hoped the words I’d written held the emotions my voice and expressions lacked. I was embarrassed to call attention to that.

Parkinson’s was the reason. Facial masking. My family doctor had diagnosed. Then the neurologist he’d sent me to wasn’t so sure. I wasn’t certain of anything. Wasn’t myself. Didn’t talk much. Voice, weaker. I’d become dull of emotion. Aside from concern and self-consciousness. Like a painter’s palette stained from past bright colors, but with only splotches of grays and browns to work with now.

When my youngest, Darren, had moved to New York, taking no books, I’d donated his childhood Paddington collection to our local library. Knowing they’d be loved. I’d wanted to go and grab his books from the stacks, I missed him so much. How to release that longing?

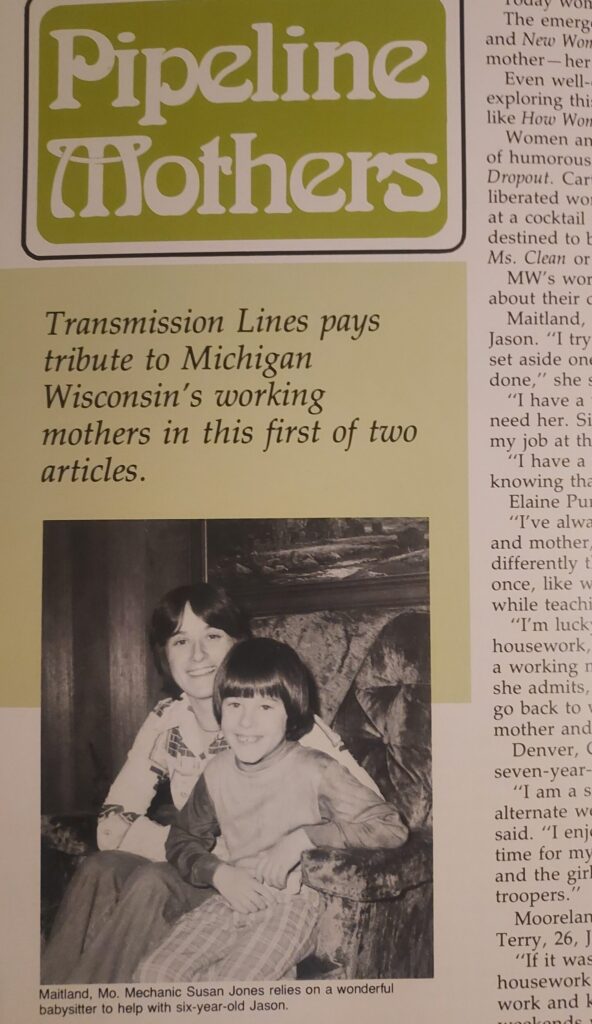

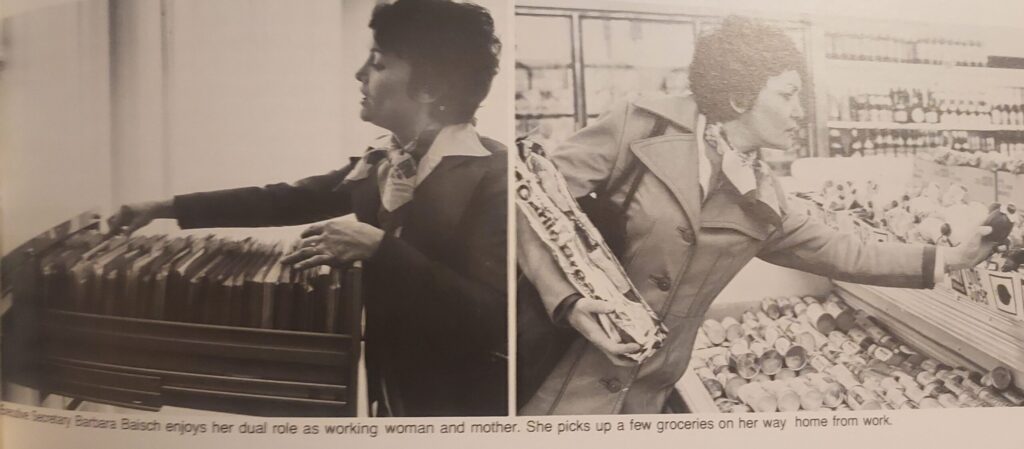

Adult enrichment classes. At the community college. Enlivening! I made a whole new set of friends. We went to readings in Ann Arbor and downtown Detroit. But I never read my work like friends did. Always pictured I would. Once I found my voice. My professional life had been spent writing human interest stories and marketing copy.

Semester by semester, I took whatever was offered. Fiction hadn’t been a fit. Sounded stilted. I was proud of some essays. One was published in a local paper. But I’d always been called to poetry.

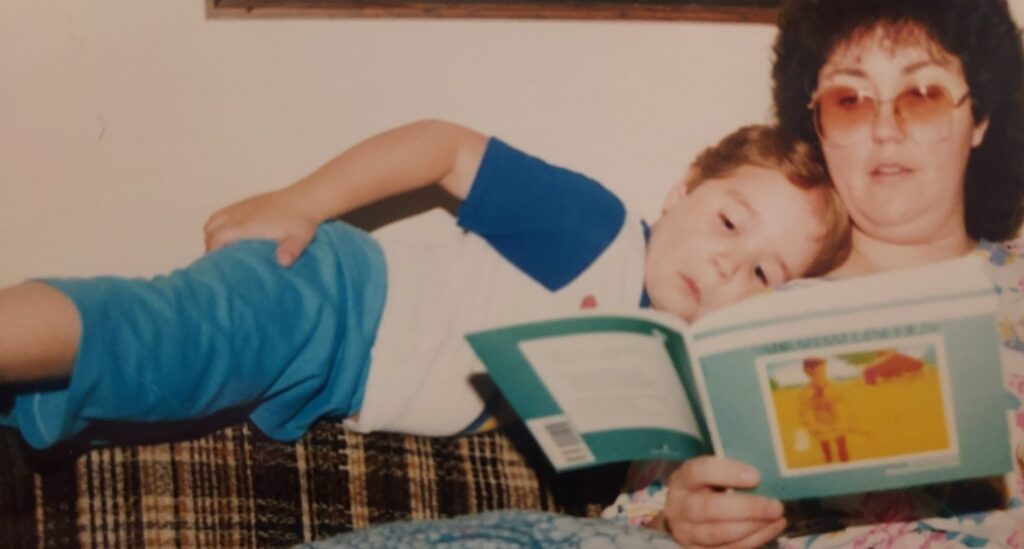

Just weeks before I’d watched my middle son, Brandon, at his MFA reception, read his work with confidence and finesse, wowing the whole full room. I knew how long he’d been rehearsing. Remembered the crowd of stuffed animals lined around the Franklin Stove, getting the best seats in the house, when he was a kid. If he could’ve been in my audience, I knew he would’ve understood how much I missed him.

Not being at Mom’s first reading—it didn’t feel right. She’d been there for mine. At the mall. When I was seven.

She was proofreader for my first published work, too. Cricket Magazine. She always encouraged me. All the way to moving to Chicago for college in my twenties, where I became part of the city’s vibrant writing community, and began performing my work frequently.

But aside from my MFA reading, during my New York years, I’d only been able to bring myself to read once. I hadn’t been this shy since Junior High, inexplicably overwhelmed (undiagnosed “severe” ADHD).

After I returned to Michigan to intervene in her health spiral, we talked about how we’d each like to start reading again soon. To be a part of more communities, see our writing through, and to perform our work, both separately and collaboratively. But “soon” evaporated into a series of crises, a decade’s worth of traumas: The heedless progression of Parkinson’s, a betrayal by a family member that pushed us toward a new beginning in Chicagoland, the isolation of the pandemic, three more major hospitalizations, learning to live with disability as she lost her mobility. Despite this, these two hearts generated a quarter million words: journals, a screenplay, our joint memoir written from both sides of the caregiving relationship, and a nonfiction book for Brandon that had broken off of our collaboration.

But it seemed less and less possible we’d ever perform again.

When Brandon told me I’d been invited to a special writing group for Parkinson’s patients, I first thought: Uh-Oh.

All year I’d been trying to find my way back into writing. And had at times. Brandon ever encouraging. The ways Parkinson’s challenges my cognition keeps changing. It scares me. Energy just won’t be in me many days. I became addicted to television. It ran my life. Eight episodes of Switched at Birth or Parenthood. Then I turned to crime shows and scared myself. Bored and ashamed of what I was filling my mind with. I tried to do cross word puzzles. I couldn’t think of what about me would interest anyone.

It was all over. No hope left for making new friends. I remember other patients in the nursing home rehab facility who would cry uncontrollably in the middle of the night. Calling out for help. It kept me awake then. And sometimes now.

Enough is enough. Do certain things for yourself. Chair Yoga, Transcendental meditation. Now’s as good a time as any. Just do it. I told Brandon to sign me up. He already had. That first week the Zoom Room was filled with people who wanted to write beyond being Parkinson’s sufferers. I didn’t think I could. Not as bravely and eloquently as the poet woman who challenged Parkinson’s to a dual of sorts. I wasn’t sure I could see through the fog. Clear my head enough to share the necessary details, to connect them. The third week, I didn’t think what I’d written was any good. Until I listened to the reactions from the group.

Brandon and I had thought the final week was going to be a live reading. I was determined. I prepared. Did my voice exercises. Motivated myself. Then we learned it was going to be pre-recorded. Which made sense (and turned out wonderfully). But I had built myself up to read in public again, finally.

So we just did it. Brandon knew of a local open mic run by a friend of his. He checked on accessibility. He always does now. We’ve learned that lesson. Day of was a bad one. We’d arrived late and waited out front of the coffee house–appropriately named Friendly–until Brandon snuck us in between readers, backing the door open and wheeling me in. But when you’re the only person in a wheelchair you know that everyone else in the room notices you. In a flash it’s my turn.

I was really doing this. Seventy-three, and

for the first time in ten years

rolling forward to read my work

to friends and neighbors

looking eagerly up to me.

It’d been an off day, her facial masking was pretty severe. But when she’d finished, the accumulated energy of the room brought out the biggest smile I’d seen in ages.

Below: more recent video of Janice reading the poem mentioned up top.